Public libraries, often referred to as the ‘people’s university’, form an integral part of the social framework. They are not just institutions for borrowing books, but also providers of information, knowledge and education, making them the social nerve of any locality. In Karnataka, public libraries are governed by the Karnataka Public Libraries Act, 1965.

The lack of a legislative review over the years has led to problems with the availability and accessibility of public libraries for all sections of society. The global pandemic has given rise to a new set of challenges that libraries are now facing, exhibiting their inability to cope with the changing times.

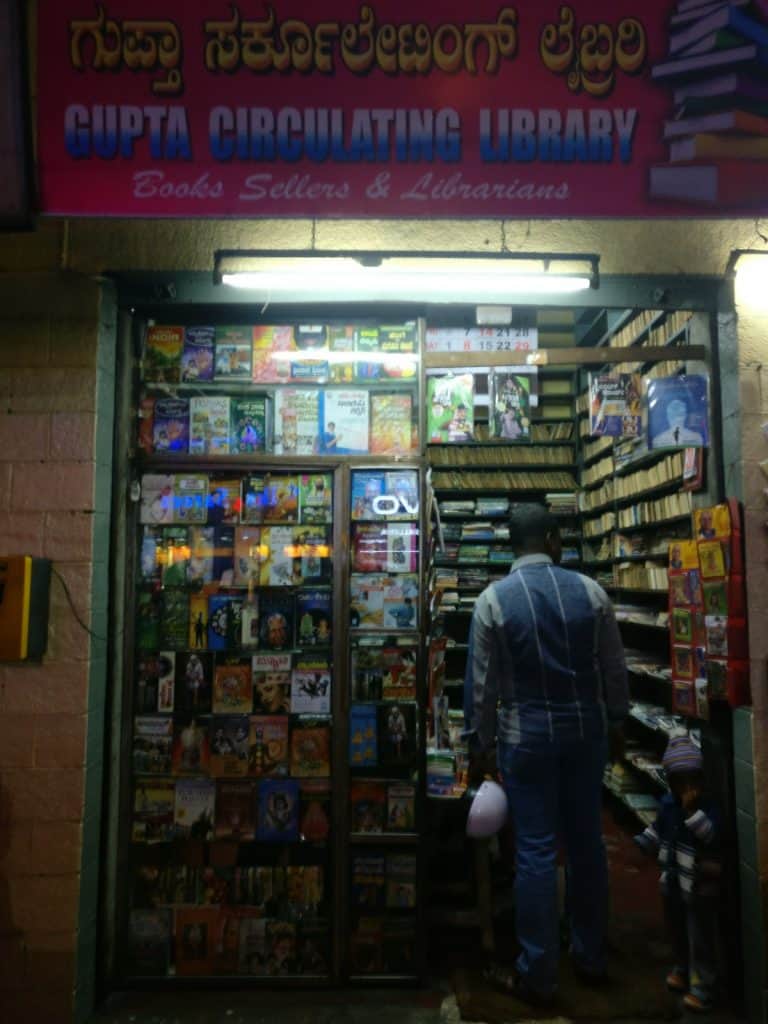

A discussion on Twitter regarding the need for public libraries and inclusive spaces in Bengaluru triggered great response, reflecting strong public interest in community spaces. There is, therefore, a need to conceptualise public libraries as user-friendly, accessible and vibrant community spaces. This requires a complete revamp of the Karnataka Public Libraries Act, 1965.

Lack of community ownership

An over-centralised system of governance for libraries defeats the concept of ownership by the local community. It is ironic that all substantial decisions, such as allocation of funds and lists of book purchases, are taken by the state level public library authorities, which often make blanket decisions for all the libraries under its realm.

Such decision making gives minimal freedom to the public libraries to spend funds and take initiatives that cater specifically to its users. In fact, any change suggested by local administrators has to be approved at the state level. This lack of autonomy for the local library authorities prevents them from creating libraries for the community, inhibiting them from thriving as inclusive spaces.

Poor financial management impacts running expenditure

According to the Act, libraries are entitled to 6% of the property tax, collected by the urban local bodies, in the form of library cess. The provision for library cess is tied to a democratic right to access and contribute to the development of public libraries, making it imperative for the government to maintain the libraries and ensure their performance is up to the satisfaction of the users.

However, owing to the lack of disbursement of funds by urban local bodies, the Department of Public Libraries finds it hard to meet the running expenditure. Additionally, the lackadaisical attitude of the officers of the BBMP in their failure to pay the cess, reflects the lack of seriousness required for the maintenance of public libraries.

In fact, in April 2022, the Urban Development Department, Government of Karnataka came down heavily on the BBMP for not releasing the library cess. The Department not only claimed that officers of the BBMP did not respond to the notices for delay in releasing the cess, but also said they skipped meetings that were called to discuss the issue. There is, therefore, a need to hold urban local bodies accountable for transferring cess to library authorities, including being penalised if deadlines are missed.

A contingency fund, provided by the state government, must be operationalised in case of delays in payment of cess. Therefore, there is a need to amend the Act in this respect.

Read more: Bengaluru’s Library System: Long way to go

Lack of access to marginalised groups

The question of access has been an important concern across the state. Most cities have failed to account for the needs of marginalised groups, such as persons with disabilities, the elderly, and women, among other vulnerable groups, rendering cities inaccessible, hostile, and exclusionary to them. This is particularly stark in the case of persons with disabilities, for whom the lack of access stems from a variety of factors, including poor urban design, a lack of usable urban infrastructure, and a lack of safety and affordability, among others.

Public Libraries in Karnataka falter as persons with disabilities, women and the elderly are often unable to access these libraries owing to the poor infrastructure and amenities. As things currently stand, Karnataka does not account for them as important stakeholders in the public library system in the state. This is largely evident in the Act as well as the 1966 Rules framed thereunder. In comparison, many other states, like Goa, have enacted public libraries legislation with a specific aim to promote and develop library services for the persons with disabilities in the state.

Most of the libraries are not accessible or welcoming to children, making it difficult for mothers, or families in general, to access libraries. There are many instances where parents and caregivers are required to work, including having to apply for jobs or attending college. In such a situation, having infants and toddlers makes it difficult to visit libraries. This resonates with many users, who have to juggle many responsibilities in their lives.

However, lessons can be learnt from initiatives across the world. For instance, the Henrico County Public Library in the U.S. installed workstations for adults with playpens attached to it. This set up offers a convenient spot for parents to work while their children are next to them in a safe and stimulating learn and play environment.

Karnataka can introduce libraries that can be children-centric spaces, especially useful in the case of mothers who wish to visit libraries. This is an example of progressive, innovative thinking to make libraries accessible to women in India, especially in the backdrop of early marriage and childbirth.

Missing links in the Act

The Act defines public libraries, but does not provide a definition of ‘library service’ or an indicative list of library services. It also does not make it compulsory for the government to ensure that such library services are provided. This creates an impediment as it is unclear what services of public libraries users can avail. For instance, the Goa Public Libraries Act, 1993, defines the list of library services to be provided to the users. This includes promoting reading habits and the use of books for the benefit of the people, promoting cooperation between the public libraries and cultural and educational institutions, promoting mobile libraries, audio libraries for the visually disabled and special libraries for the hearing impaired, text-book library, children library computerisation, micro-filming of rare documents, among others.

Some state legislations, such as Kerala Public Libraries Act, 1989, Chhattisgarh Public Libraries Act, 2008, also specify the functions of different levels of libraries such as the State Central, district, and village libraries. This allows additional responsibilities and more stringent standards to be placed on Central, state, and district libraries, which can then act as models for the remaining libraries in the state.

Despite Karnataka leading the digital public library movement in the country, there is no legislative backing for the establishment or management of digital public libraries in the state. The existing legislation needs to account for the same, as it currently makes no mention of ‘digital libraries’, ‘computerisation of library books’, ‘electronic media’ or any other form that indicates that the Act promotes the digital public libraries movement.

Inability to deal with public health emergencies

The Karnataka Public Libraries Act, 1965, is not equipped to deal with public health emergencies. The pandemic created increased barriers to engaging with library resources and spaces, as public libraries in Karnataka were shut for five months in 2020.

The global pandemic has had a significant impact on the lives of the people in Karnataka, giving rise to new challenges for libraries, which are unable to cope with the changing times. Therefore, there is a need to re-envision the role of public libraries. This transformation from knowledge centres to “libraries for the community” emphasises the role of libraries in today’s world and their ability to act as healing places for the people.

For instance, The Community Library Project (TCLP), which operates in four centres for low income communities in Delhi and Gurugram, identified themselves as an information hub when the pandemic hit and became a coordinating agency. During the first wave of the pandemic, they called all the members across their libraries to identify their needs and keep a track of them as they moved to, or planned to move to, their hometowns. Therefore, to become a true resource centre for the community, public libraries must first make efforts to assess and understand the information needs of the community.

Read more: How have Chennai’s public libraries been impacted by the pandemic?

During the pandemic, the Bansa Community Library & Resource Centre in the Hardoi district of Uttar Pradesh inculcated reading habits and created a community of book lovers.

Hasiru Dala, a social impact organisation working with waste collectors in Karnataka, started the Buguri Community Library to create and nurture spaces for children of waste collectors. During the COVID-19 induced lockdowns, this library harnessed technology to reconnect children with libraries. The library also tried to keep the children engaged through activities such as Q&A sessions, book reading, drawing, music, etc. Therefore, data reflects that these community libraries, which often do not have sufficient funding, have been able to provide for the community as opposed to public libraries, which have better funding in comparison.

The way forward for public libraries in Karnataka

While the current legislation caters to accessibility of information to all sections of the society, to a certain extent, a lack of review of the same poses pertinent problems. This Act is a set of administrative rules lacking the essence of a social connection with the actual public library system.

The public library legislation should not be static and needs to be reformed constantly, in accord with a changing society. This Act has not undergone a substantial change post its enactment in 1965, and hence, the Act and the Rules made thereunder need to be revisited.

Tamil Nadu has constituted an eight-member high level committee to suggest amendments to the Tamil Nadu Public Libraries Act, 1948. The acknowledgement of these issues by the TN government is a step in the right direction to improve its public library services. The government has decided to include the general public in this process. A systematic and comprehensive questionnaire has been posted on its website for the public to provide any recommendations. This decision to reach out to the main stakeholders of these libraries instils a sense of confidence in the state’s commitment to re-evaluate and reform the public library service to make it more inclusive and functional.

It is suggested that the Karnataka Government undertake such consultations with both field experts and the general public to ascertain the problems that plague public libraries. An inclusive consultation process would mean the library users could flag issues of accessibility, inclusivity as well as day-to-day problems faced by them in the use of these services. It would also give the experts a chance to critically evaluate and rethink the structural mechanisms that are employed to run these libraries. Overall, it would result in a wide range of suggestions and recommendations that would help improve the condition of public libraries in the state.

Karnataka’s aim of creating ‘digital powerhouses of knowledge’ has no meaning until these powerhouses are first made better and presentable. To foster the development of libraries as inclusionary spaces for community engagement, as the state aspires, a lot needs to be done to fix the existing structure. In a society that is marred with technological innovation and the internet, it becomes imperative to address people-centric, grassroots community driven issues.