Garbage generated in Bengaluru’s markets big and small can be a star, according to VEDAN, an NGO working on creating awareness among people on waste management issues.

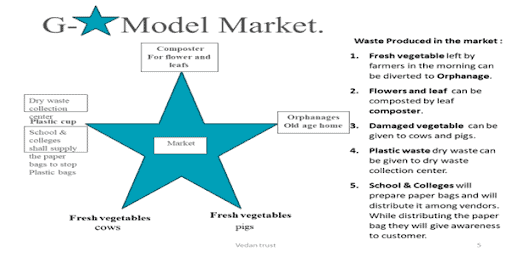

Named G-Star, the suggested model, which came out of Vedan’s study of K R Puram market, brings together people who produce waste and those who can make productive use of it.

The G-star model can reduce the mixed waste that goes to landfills. This waste can be distributed to all stakeholders in a desired form by collecting it directly from vendors at the market as and when it is produced.

The K R puram study showed that piggeries, cow and sheep owners in particular are ready to take wet and dry waste generated in the markets as feedstock for their animals.

The authors describe how Vedan went about implementing the G-Star model in the Madiwala market:

Implementing the G-star model

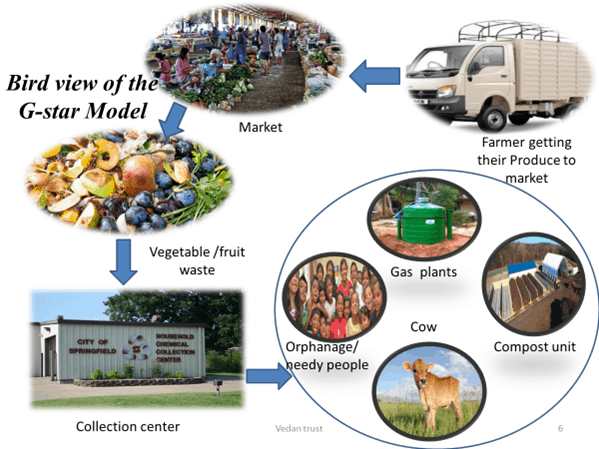

As shown in the image below, farmers bring their produce to market and vendors buy from them. Farmers spend a limited amount of time in the market to sell their produce and leave whatever is unsold, often fresh produce, in the market itself. This leftover fresh produce can be diverted to orphanages. The waste that cows and pigs can consume can be directed to the respective owners. The remaining wet waste can go to a compost unit. Dry waste, which is just one percent of the total waste, can go for recycling.

In order to divert waste at the right time and in the right manner to the respective stakeholders, we propose a collection centre. The waste is collected in crates in trolleys directly from vendors and stored at the collection centre, which will be the focal point for its distribution.

Implementing the G-star model at Madiwala Market

The busy, vibrant Madiwala Market has ensured livelihoods to hundreds of vendors and farmers in and around Bengaluru ever since it was set up around 40 years ago. Though the stray livestock around the market devours much of the wet waste generated, waste management was chaotic.

Vendors and farmers either left unsold produce at the point of sale or dumped it at a common area in the market. Almost a truckload of waste used to be lifted from the market every day. And pourakarmikas were left to manually sweep and tidy up the area.

Yet putrid waste would constantly be found lying around in the market. Owners would leave their cows to scavenge on this waste.

When we started working in Madiwala, our primary objectives were to:

- Bring about a proper waste management system in the market

- Achieve visual cleanliness, with no black spots

- Ensure segregation of waste at source so that waste could be given to cow owners, piggery and sheep instead of sending it to the compost unit. Large numbers of livestock are present within a 5-km radius of the market.

- Inculcate the habit of segregation among vendors and other stakeholders

- Prevent mixed waste from going to the landfill

- Avoid single-use cups

How did we achieve this?

We then began identifying vendors in the market, and the type and quantity of waste each of them generated.

There are 401 shops in Madiwala Market. The types of shops are retail (16), vegetable retail (364), fruits retail (12), and flowers retail (9).

Both dry and wet waste is generated here throughout the year. Dry waste produced per day is 200-500 kg. Wet waste produced, as calculated in February to March, in the lean period (usually February to May when farm production is less) is 7,000-12,000 kg per day and peak period (the monsoon and festival season that follows) is 18,000-22,000 kg per day.

Once the vendors and the volume of waste to be managed is identified, we had to devise a plan of action which involved various stakeholders and possible changes in the processes.

Changing pourakarmikas’ shift and roster system to be adopted

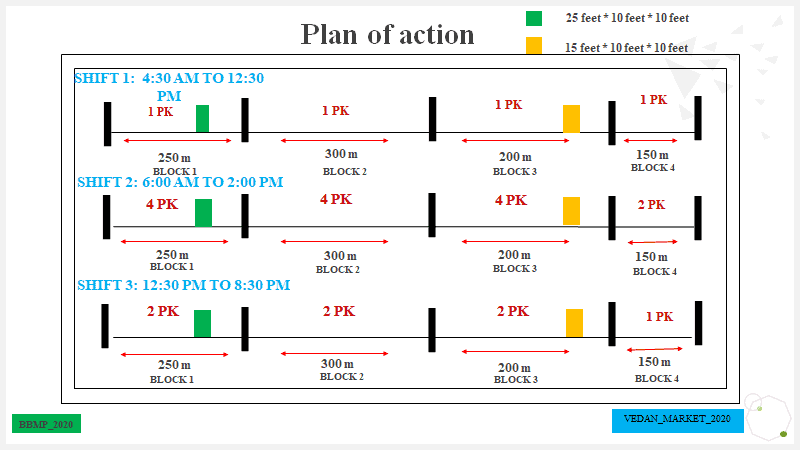

Based on a time-motion study to understand the work done by pourakarmikas throughout the day, we divided the market into four blocks. These blocks were decided based on the area they occupied and the quantity of waste generated in each block.

We began by changing the working hours of the pourakarmikas as the market operates nearly for 18 hours a day and laid out a standard operating procedure for them.

The table below indicates, the work shift timing of the pourakarmikas was revised from the previous one 6:00 am to 2:00 pm shift to three shifts between 4:30 am and 8:30 pm across four blocks, each covering 150-300 metre.

The previous shift required seven autos, but now only one auto is required. Additionally, the pourakarmikas now get one weekly off; earlier, they had half-days off on Wednesdays and Sundays.

To implement such change, it is important to work with Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP). BBMP Special Commissioner (Animal Husbandry and Solid Waste Management) Randeep Dev supported this model.

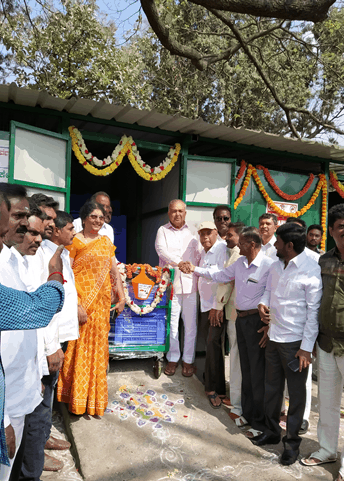

Setting up waste aggregation centers

Two waste aggregation centers were set up to store waste collected in crates and trolleys by the pourakarmikas from the four blocks and to store the waste to be sent to cattle owners and piggeries. Other waste collected is transported by compactors for unloading at the compost plant at Chikkanagamangala.

Waste Aggregation Center -1

Waste Aggregation Center -2

For every block, work has been allotted according to the shifts of the pourakarmikas who take the crates in the trolley and categorize it as wet waste.

The waste then is further sorted into categories which can be consumed by cows and pigs and put in separate crates, and those which will go to the compactor is collected in separate crates. Therefore, while collecting itself the waste is segregated. Dry waste is collected separately in a bag.

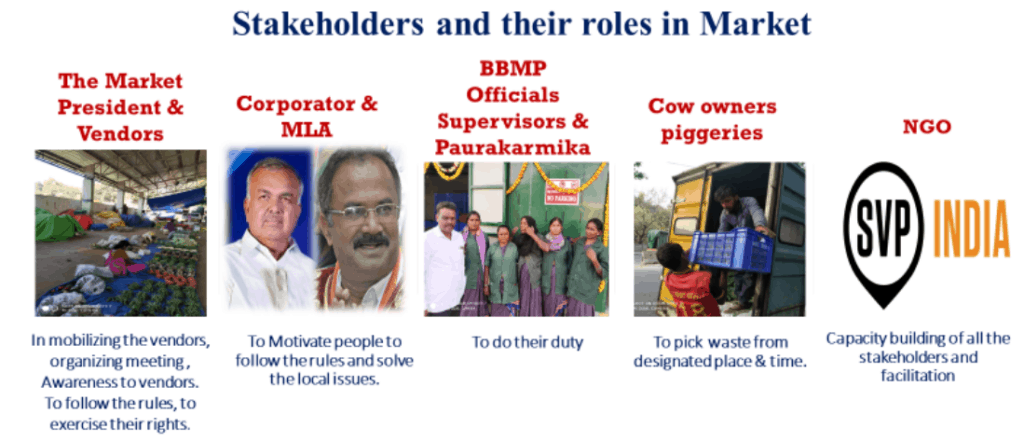

Working with stakeholders

Work at such scale is not possible without the help and cooperation of various stakeholders. We have had to work with a range of organisations and individuals to make this happen.

We worked with BBMP Special Commissioner (Solid Waste Management) Randeep Dev who believed in this model and encouraged the pilot interventions. He also decided to bring in a roster system and three working shifts for the pourakarmikas. BBMP (South) Joint Commissioner Veerabhadra Swamy and Narasarama Rao, Superintending Engineer for Solid Waste Management, helped in the ground level facilitation and building the shed.

BBMP Solid Waste Management (BTM Layout) Assistant Executive Engineer (AEE) Santosh was an exceptional officer throughout this project. He used to come to the market at 4:30 am and keep a watch on the offenders, create awareness among the vendors, and motivate pourakarmikas and their supervisors. Santosh and his team have played an important role in sustaining the intervention.

This was indeed a community initiative as the market presidents, Pyare and Akmal, gave their own office space to keep our waste filled crates until BBMP built the shed. Solid Waste Management expert, Manjula guided the team and trained the pourakarmikas. We were thrilled when students of Krupanidhi College and Vemana Institute of Technology came in and helped in raising awareness and painting the walls of the market.

MLA Ramalinga Reddy, Former BBMP Mayor and Corporator Manjunath Reddy, and Former Corporator Chandrappa also extended their support.

Social Venture Partners India (SVP India) played a key role in pushing things forward from the political front. They helped us with the funds required for the trolley and shed to kick start of the project. It was because of their continuous follow up that roads were laid, toilets were opened and plants were grown on the divider.

Padmashree from SVP India monitors the markets and has been the key in bringing in all the stakeholders on the same platform, which truly is commendable. She also motivates the pourakarmikas and supervisors to work diligently, and follows up when they don’t do their job properly.

With such support for the model, 95 per cent waste segregation has been achieved at the market, and seven major black spots are cleared.

An average of 3000-5000 kg mixed waste used to be dumped at the black spots and loaded into garbage vehicles every day. This has now come down to 100-500 kg. Of the four blocks, block 1 has been a challenge since residents of neighbouring Siddhartha Colony would dump waste next to the toilet area. BBMP collection in this area was not regular, and the market supervisors were not vigilant. One supervisor is a BBMP employee while others are employed by the contractor and paid by BBMP.

Cost of setting up the system

To implement the model, equipment and infrastructure such as trolleys, shed and crates will need to be procured. The capital cost involved is Rs 3,50,000 to Rs 10,00,000, depending on the size of the market.

The Total capital cost to set up this waste management system at the Madiwala Market was Rs 5,50,000.

Social Venture Partners India (SVP India) contributed Rs 1,95,000 for the broomsticks stand, four trolleys, dining table, dustbins and cementing of the entry and exit points. The market association contributed Rs 75,000 for the second Waste Aggregation Center. The remaining amount was contributed by BBMP for 350 crates and one Waste Aggregation Center.

The system works smoothly now

The pourakarmikas have realised the importance of teamwork and are working systematically. The vendors too have been brought into the system and are contributing with heightened awareness. On a usual day, ~ 1000-1300 kg of waste goes to cows, pigs and sheep.

After educating everyone about the environmental damage paper cups cause, and sustainable alternatives such as steel cups, paper cups are now banned but since COVID these cups have come back in use.

We had also seen some behavioural changes such as the practice of taking Rs 500 monthly from the pourakarmikas had stopped, but this issue has resurfaced again.

Since pourakarmikas are now working with fresh waste, instead of stale and harmful waste, we expect they will not be exposed to health risks. The toilet repair work too has been taken up which will ensure a safe and hygienic facility for the pourakarmikas, vendors and the visiting public. It will be open to the public soon.

We do face challenges

While much has been achieved, there are several challenges that we need to work on with the support of stakeholders. Here are some challenges faced:

Challenges faced by supervisors

- Poor implementation of the ban on paper cups now due to COVID.

- Maintaining consistency in daily outcomes.

- Ensuring that the standard operating procedure is followed

- Maintaining documents is a challenge.

Challenges in clearing black spots

- One black spot near the public toilet is yet to be fixed. Also, pushcart vendors throw 2-3 bags of wet waste from the market here at around 3 am everyday.

To resolve these challenges, we plan to focus on the following in the coming days:

- Capacity building of pourakarmikas and supervisors: A sense of the importance of teamwork and time management needs to be inculcated. Pourakarmikas need training on how to use bank accounts and ATM cards. We also need to educate pourakarmikas about their rights.

- Infrastructure development: Buying additional crates if required, and buying trolleys for collection of waste swept by the pourakarmikas

- Waste diversion: We expect half the wet waste generated to be diverted to cows and pigs since this will be a more sustainable practice even in the future as demand from cattle owners and piggeries will be consistent.

Additionally, we are working on creating a parking space, mechanisation of the waste management process, and beautification of the market.

As part of Swatch Bharat,suggesting to

Use a Mobile Unit ‘Wastemincinerator which can also convert Waste to Clean Air,a unit Collects and Disposses Non Recyclable waste JUST IN TIME avoiding

COLLECTION CENTERS amd its transportation to Landfills etc.

Anything that is free In INDIA does not have value. A small penalty should be imposed on violation by traders.

Total van on use of all types of plastic covers irrespective of micron should be insisted. People should be insisted to bring their baggages. One entry and exit points should be established for checking.