For someone who lives in Bengaluru, chances are that there is a public library not more than a 20-minute ride away. Out of 80 public libraries in Bengaluru, 79 fall within a 20-km radius from the State Central Library located in Cubbon Park.

Interactive map of libraries in the city

The Department of Public Libraries website lists 458 government-run libraries in Bengaluru. These include Gram Panchayat libraries, a Travel library, Traffic and Sewage Libraries. About 200 of these are reported to be public libraries.

The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA), contextualising the role of libraries in the fulfilment of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), recommends one library for every 3000 people. While no Indian city comes anywhere close to meeting the ILFA’s recommendation, Bengaluru is one of the better-off cities as far as the number of public libraries is concerned.

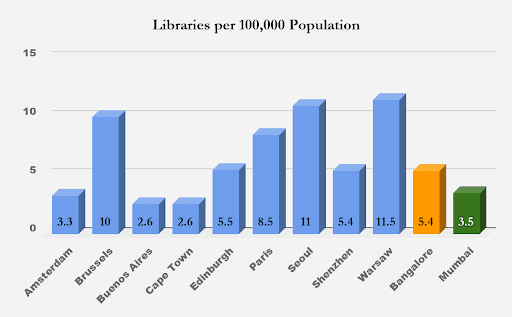

For a city of 84.3 lakh people (2011), Bengaluru has 485 libraries, which is 1 library for every 18,406 people. In comparison, Mumbai, a city of 1.8 Crore people (2011), has 622 public libraries, that is to 1 library for every 28,938 people. Both Bengaluru and Mumbai however, fare quite well compared to cities in other countries.

“There are over 200 libraries in Bengaluru in five zones, including Gram Panchayat Libraries and Vachanalaya (reading rooms)”, confirms DH Kesari, Deputy Director at the City Central Library in RPC Layout, Vijayanagar.

If one thought that libraries had long ceased to be the go-to places in the City, one should step into the impressive two-storey building that houses the City Central Library at RPC Layout. This main branch for the entire West Zone has 11,940 members and a footfall of 800-1200 people a day, mostly students preparing for civil services exams.

“Every other place you can go to, you have to pay money. But libraries are a place where we can come for free,” points out Mahesh Manohar Sajjanar, a businessman who has spent over 20 years working with Bengaluru’s public libraries as a supplier of maintenance services. Lifetime membership at the library comes at Rs 100 – 200, which is refundable.

What’s more, the place has a well-maintained garden, offers facilities like drinking water, toilets, well-stacked reading rooms and even a room with computers.

“I come here every day because I love reading, but honestly, things could be much better. That chair (pointing to the chair intended for the attendant) is empty most of the time and the infrastructure is lacking,” says Prakash, a retired banker who has been a frequent visitor for over six years.

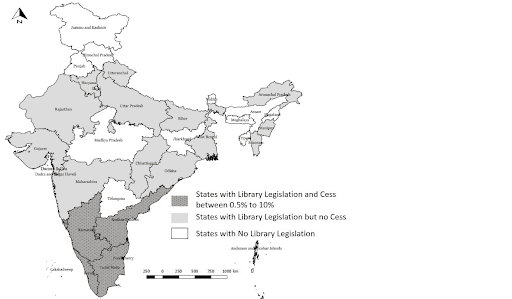

Spaces such as the RPC Layout Library owe their origin and existence to the Karnataka Public Libraries Act, 1965, which itself came about after the Madras Public Libraries Act of 1948. Eighteen other states in the country followed suit and passed State-level library legislations. Five southern states have also introduced a library cess – a tax intended to be the primary source of funding for public libraries.

Karnataka is one of those five states that are considered progressive as far as public library systems are concerned. A simple comparison with Uttar Pradesh illustrates this point well. It was reported that UP, which has a population of more than 200 million, supports only 70 public libraries, while Karnataka, with a third of UP’s population, boasts of around 7,000. As of 2017, UP spent roughly Rs 24 crore on libraries, while Karnataka, which charges a library cess, spent about Rs 186 crore.

Misleading data

Numbers paint a rosy picture of the public library system in Bengaluru. But even libraries like the one in RPC Layout are struggling. Smaller public libraries are languishing in a state of despair.

Preedip Balaji, library consultant and researcher at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements, Bengaluru, along with his colleagues M S Vinay and J S Mohan Raju, published A Policy Review of Public Libraries in India last year. He notes that finding relevant data was the first hurdle.

Even basic data pertaining to the number, location, allocation of funds and expenditure for libraries is not available for most states and cities in the country. For cities like Bengaluru, where it can be found, there is considerable confusion and contradiction.

For instance, while the Karnataka government’s Department of Public Libraries website claims there are 458 public libraries in the city, the same department has plans to digitise Bengaluru’s “200” public libraries, according to a news report.

Country-wide data is also insufficient. According to the 2011 census, there are over 76,000 libraries in India. In Karnataka, the number stands at over 7,239. These high numbers seem to suggest a robust public library system but there is no way to account for how many of these libraries are actually functional.

Where goes the Cess?

Despite the library cess collected by the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike, public libraries do not receive sufficient funds. As much as 6% of the property tax collected in the State by municipal bodies and corporations — as Library Cess — is supposed to go to the Department of Public Libraries.

This past year alone, the BBMP collected a record Rs 2510 crore in property tax. Yet, the BBMP has not released the library cess to the Department of Public Libraries in over six years. According to news reports, the owed amount has crossed Rs 400 crore.

As if withholding funds was not bad enough, the BBMP now plans to take over the administration of public libraries in the City. The move has been criticised widely, considering that the BBMP already has enough on its plate.

Sajjanar thinks the amount is much higher. “They are reporting Rs 400 crore, but the real number is closer to Rs 600 crore.”

That explains why even the seemingly well-run public libraries like the RPC Layout library are also short of funds. “We go asking for funds to the BBMP, but they only give it in parts…if we get funding, we can do development works and even digitise. This year, they gave 10 crore per zone,” says D D Kesari.

The Rs 10 crore per zone is apparently a welcome hike. Funding for a zone — which can have over 40 libraries — has normally been around Rs 5 crore per annum. Little wonder that the state of smaller libraries is worse, as The Economic Times reported. Without money, they cannot carry out basic repairs, develop new buildings or implement the 20-year old plan for digitisation.

There are a host of other issues too: lack of morale, training and capacity-building. Preedip says “We (academic librarians) have active associations and networks where we share resources. That’s missing for public librarians.”

Like in many government departments, temporary staff is a majority. While permanent employees receive regular salaries ranging between Rs 20,000 – 40,000, they constitute only 20-30% of the workforce. The other 70-80% is made up of ‘temporary staff’ employed on a contractual basis. The nature of their employment denies them any perks and regulatory protections of permanent employment. And their monthly remuneration is an abysmal Rs 6500.

Much as they are short-staffed, zonal deputy directors like Kesari don’t have the power to appoint permanent employees. New positions can be created only by the state government and involves convoluted bureaucratic processes.

The Centre cannot hold

A highly centralised system of governance defeats the concept of ownership by the local community. If local administrators wants to change something, they cannot. Everything has to go through the state level. Even though most of a public library’s work happens at the neighbourhood level, there is little to no agency for library employees. The situation for other districts is worse, as they are at the mercy of the capital..

“There is no comprehensive system of public library governance…lots of division and fragmentation, which means that a lot of them are functioning in silos,” notes Preedip.

Considering the lack of funds and a highly centralised structure, it is staggering that public libraries have survived as an institution. Despite the rise of the internet and new public spaces such as shopping malls, they are struggling to foster a reading culture while acting as equalisers in a knowledge society.

What spaces they leave uncovered are being filled by libraries run by NGOs and voluntary agencies, not to mention commercially-run private libraries. “They are doing the job that government-run libraries are supposed to do,” laments Preedip.