Poor living and work conditions. Poor nutrition. The inevitable outcome — is poor health. Bangalore’s migrant workers, many of whom are from far-off states like Bihar, seem to be permanently mired in this cycle. With little hope of any relief from the state.

Health is a particular worry for many, given their poor working conditions. The contractors who employ the workers rarely help when they fall ill. Neither are the workers able to access any of the central and state government schemes that offer them free, or cheap, health care.

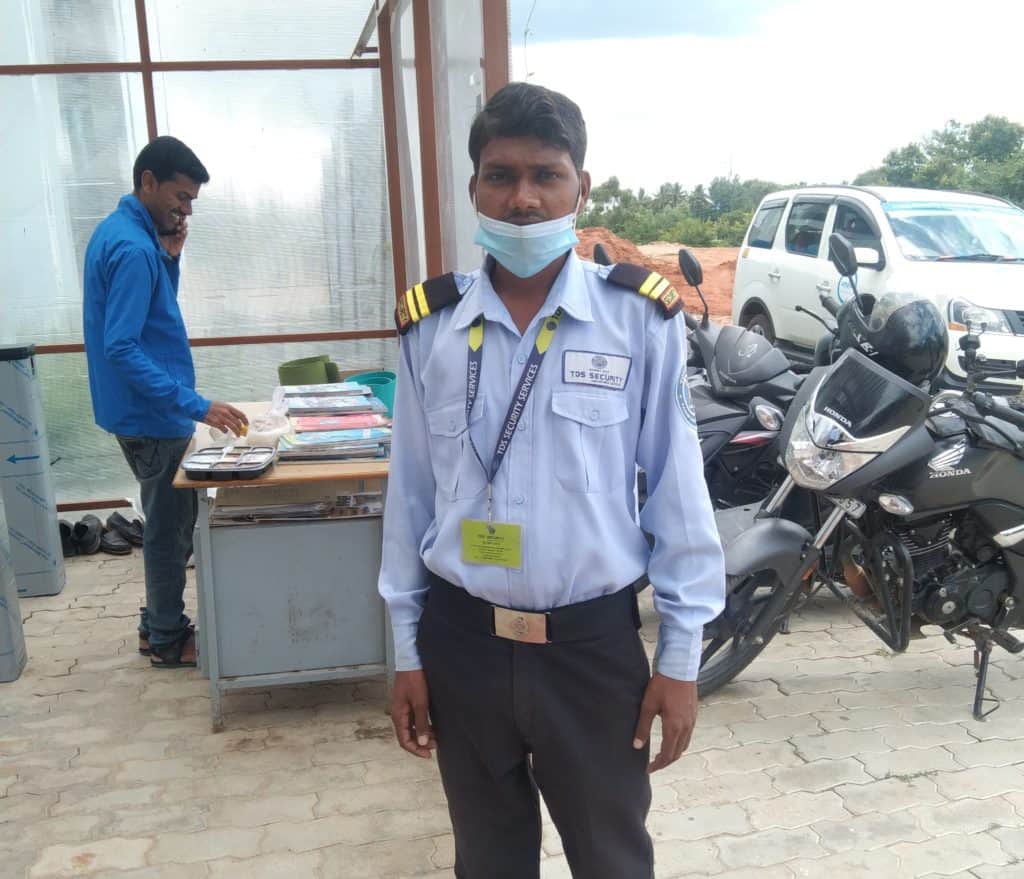

Mohammad Amar, 22, from Purnia in Bihar came to Bangalore in January and is working as a security guard with the TDS agency. He puts in a 12-hour stint daily, without any weekly off day, from 8 am to 8 pm in whichever location he is given for the day. He gets a monthly salary of Rs 15,000 of which he sends Rs 5000-8000 back home to support his family.

Amar’s employment conditions do not include any paid medical leave though occasionally he does get paid sick leave depending on the severity of his illness. His company bears medical expenses only if he develops a health issue in the line of duty. “The company does not bear off-duty medical expenses”, says Amar.

Read more: Migrant workers deal with unhygienic living conditions, poor nutrition

No health insurance card

Amar’s ageing parents back in Bihar have a health insurance card issued under the Ayushman Bharat scheme. But Amar does not. And being a newcomer in Bengaluru who can’t speak the local language makes it “difficult and challenging for me to access health services in local PHCs”.

For registration at a local PHC, Amar needs a local address proof which he does not have as his Aadhaar card has his home address. Amar says he does not know of any other migrant worker who has availed of health care at a government clinic. Amar, and others like him, are thus forced to spend from their pockets at private clinics.

Another migrant worker, Tej Prasad Giri, 48 from Assam, came here to Bengaluru with his family eight years ago. He has been working as a security guard for the past six months at a construction site in Sarjapur where 300 migrant workers live in tin sheds. Tej Prasad’s salary is Rs 13,000 per month and he works a 12-hour shift from 8 am to 8 pm. His duty is to control the entry and exit of the labour colony.

Tej Prasad himself lives in a pukka house in Billapura; he has three daughters (all married) and a son. One daughter and son-in-law live in Bengaluru. The son-in-law, too, works as a security guard at different sites. Neither Tej Prasad nor his family members have any health insurance cards. He did have health insurance provided by the previous company he worked for. But not with his current company even though government rules specify that contractors have an obligation to provide health care to their workers.

Tej Prasad contracted COVID-19 during the second wave and his earlier company covered his treatment expenses. “Magar iss company me kuch nahi milta (But this company gives nothing),” says Tej Prasad.

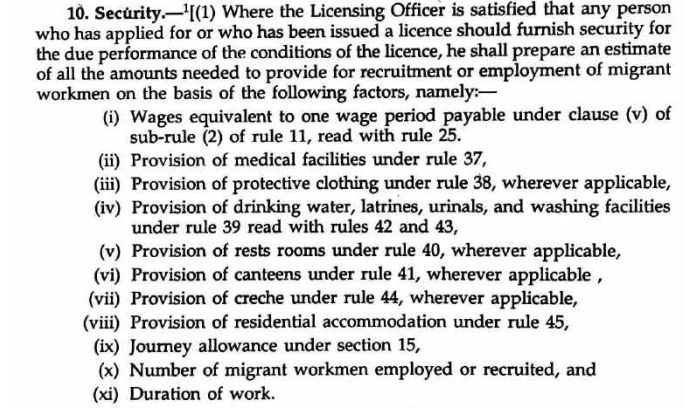

The sad litany of having to fend for themselves when they fall ill goes on despite the several laws and rules governing the obligations of the contractor to provide health benefits and proper working conditions (see image)

Healthcare schemes for workers and how to access them

There are various schemes under the central government, including Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana for Below Poverty Line (BPL) familyies which provides health coverage up to Rs 30,000 for five members of the worker’s family.

The latest central initiative is the Ayushman Bharat National Health Protection Mission which provides Rs 5 lakh coverage per household each year. It also provides cashless benefits from any public or private hospital in the country which is associated with this scheme. See details here.

Workers need to take the following steps to access this scheme:

- Go to the NHA portal and log in to mera.pmjdy.gov.in.

- Enter mobile number and captcha code.

- A one-time password will be sent to the mobile number.

- After entering the OTP, select the state of residence and fill in the worker’s name, mobile number, ration card number, or Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna URN number.

- If the worker’s name is in the list, it will show up on the right-hand side of the page.

- Click on the ‘Family Members’ tab to find beneficiary details.

- Required documents include respective special category certificates, age proof documents, family structure, identification details, contact information, scanned copy of Aadhaar, income certificate and caste certificate.

Lack of awareness of health schemes

But most workers are unaware of such schemes. “I don’t know about this scheme and lack of awareness among workers is very much prevalent in the informal sector,” says Nitai Das, who hails from Bengal.

The contractors could not care less about their worker’s injuries or other health issues, leaving them to fend for themselves even when they get injured while on duty.

Like Nitai Das, 32, who left his two children back home to work as a tiles setter in a Bengaluru construction site. For an eight-hour shift from 9 am to 6 pm he gets Rs 550 per day for 26 days a month. He too has no access to government health schemes. Two weeks back, he was injured at work when a rod pierced his left leg. Nitai spent Rs 4000 from his pocket to get his leg treated as the contractor did not provide any monetary help, instead telling Nitai that his inability to work would be treated as leave without pay. Nitai is resigned, “Ab kya karenge, kuch nahi milega to gao nikal jayenge (What will I do now. If I will not get anything then I’ll go back to my village)”.

Read more: Costly private health care more a necessity than a choice for poor, pregnant migrant women

No choice but to migrate

Another migrant worker Shivji Sharma, 40, from Khagaria in Bihar works as a carpenter on the same construction site as Tej Prasad Giri and earns around Rs 21,000 per month. Having joined just 10 days ago, Shivji has no permanent home and stays in the labour colony at the site. He has four young children and a wife in Bihar and sends them Rs 15,000 per month. He too has no medical insurance or health card and has to pay from his pocket for any medical treatment.

Arun Kumar, 36, also from Bihar lives in the same labour colony with his wife Karuna and two small kids. Both he and his wife do masonry work. He came to Bengaluru after the pandemic and doesn’t have health insurance or the Ayushman Bharat card.

“Mere dono bacche har mahine bimar hote hain jis mein Rs 2000 ki dawa lagti hai, kisi se kuch nahi milta yahan (Both my children fall sick and medicines cost me Rs 2000 monthly, nothing is provided by anybody)” says Arun. He is a Hindi graduate, and Karuna has studied up to 9th class. “Hum choti zaat ke hain, hamare pass na zameen hai, na ghar hai na hi koi madad karta hai, tabhi yahan ayye hain kam karne (We belong to a lower caste, we have neither land, nor house, no one helps us, which is why we came here to work)” adds Kumar.

Not surprisingly, these workers are mostly unaware of their entitlements/rights to government health care and hardly have any idea of how hospitals and insurance providers function. Plus they have difficulty confirming their identity/eligibility, their difficulties multiplied by their unfamiliarity with the local language.

Also, there is hardly any state-sponsored outreach programme to create such awareness among these workers. The result – the same miserable cycle of poor living conditions. Poor nutrition. With the inevitable outcome, poor health.