It was only last week that work hours returned to “normal” for Sajida, an Accredited Social Health Worker (ASHA), also known as Community Health Worker, who lives in Mahalakshmi Layout.

As with all ASHA workers, she was part of the critical front line; keeping her ears to the ground and eyes peeled for any sign of Covid-19 and its spread in her locality.

Since March, when the city recorded its first coronavirus case, Sajida has worked up to 16 hours a day, surveying neighbourhoods and tracing contacts of those who tested positive.

Although Covid-19 cases and positivity rates have dropped multi-fold since, her work hours continue to stretch into the night. “The national programmes against tuberculosis and malnutrition are usually conducted in July, but this had been delayed till November-end. After the Covid-19 wave receded, we had to dive into the pending work and meet the stiff targets,” she says.

The remnants of her Covid-19 exhaustion still lingers. Talk of a possible second wave raises anxiety. “My thyroid issue flared up during the scamper of the first wave. We had no food, no water, no protective gear. We didn’t even get paid the incentives we were promised. If there is a second wave, shouldn’t the government be placing their attention on front line workers like us?” Sajida asks.

Delhi’s health infrastructure was overwhelmed by the second wave there. Bengaluru’s city administration, however, has been confident about tackling a second wave. Karnataka’s technical advisory committee expects the second wave to hit the state in January-February.

“Bengaluru better prepared”

“We expect Bengaluru to become the focus of this because of its population. Looking at the history of pandemics, it is inevitable. We can’t prevent it, but its severity is in our control,” says S. Sachidanand, vice-chancellor of Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences. Sachidanand headed the State Death Audit Committee that analysed ways of reducing mortality due to the airborne viral infection.

“But, we are in a better position to deal with the second wave than we were during the first. The health infrastructure has vastly improved and we know how to treat the disease better, to reduce mortality. What we need is to ensure enforcement of social distancing norms and mask-wearing, particularly if colleges and schools open up,” he says.

The chaos of the first wave paved the way to better prepare for the second wave, he says. Bengaluru’s hospitals were overwhelmed, ICUs were at capacity, oxygen supply was a concern, front line workers were overburdened, while even ambulances were in short supply.

Adding to the chaos were ever-changing rules that saw city authorities imposing severe restrictions in large areas and mandatory isolation at covid care centres. Protocols are no longer extreme It was only when cases reached a peak that the city’s managers get some administrative clarity on division of work and coordination with private hospitals.

“People didn’t know much of the disease and how to contain it. We had to learn fast, ramp up everything and get additional manpower. Though the first wave ended, this infrastructure and resources remain as is, and will continue till February or whenever the second wave abates,” says Dr B.K. Vijendra, Chief Health Officer (Public Health), Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP).

Currently, just a third of the Government quota of beds for Covid-19 positive patients are occupied, and around half of ICU and ICUs with ventilators are available in government centres.

“There are more than enough ICU beds. Oxygen availability is not a problem. Through earlier surveys, we know the vulnerable population in the city and we are monitoring the spread of the disease among them. This level of surveillance will ensure that we can ramp up hospital infrastructure if we detect increasing number of cases before the second wave,” says Dr Vijendra.

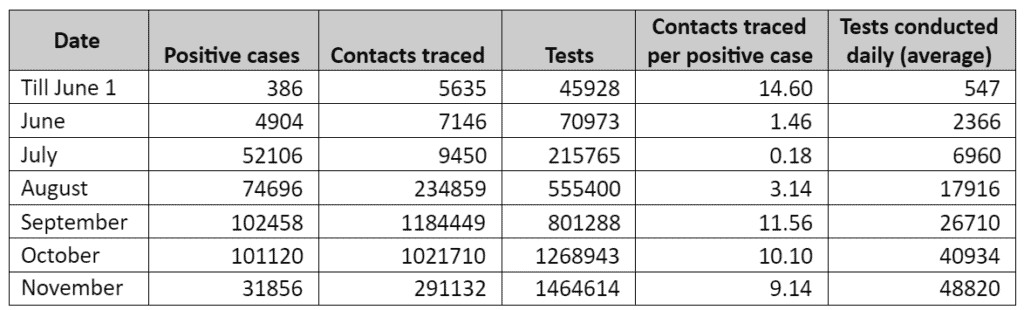

The Technical advisory committee (TAC) had recommended aggressive testing and mandatory testing of SARI (Severe Acute Respiratory Infection) and ILI (Influenza-like Illness) cases. BBMP data shows that testing remains high and even surpasses the daily average tests conducted during the peak of the first wave.

However, BBMP is lacking in meeting the TAC’s recommended target of tracing and testing 20 contacts per case. BBMP traces, on an average, 9 persons per positive test, lower than 11 persons in September which marked the peak of the first wave in the city.

Bengaluru’s Covid-19 trajectory

Warriors need morale

“We are better organized for sure. Administrators and health workers know their roles. They have the capacity to respond,” says Dr Himanshu, epidemiologist and researcher in global health, who worked with Bengaluru’s authorities during the first wave.

The Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike’s task force to battle Covid-19, which included guest experts such as Dr M Himanshu, has not met since October. “But, as we have seen in Delhi, which was equally well-prepared, the system can be overwhelmed. The second wave peak was higher than the first, and with more deaths. We can’t be lax about this. We should revive the broader task force and make it active,” he says.

A concern that still plagues the system is the exhaustion among community health workers. “In case the second wave is worse than the first, we can’t ramp up oxygen capacity or build ICU ventilators overnight. Instead, you’ll need front line workers to be active and to contain the spread. But they are an exhausted lot, and there is no financial incentive we are giving. They are demoralised. Even though the cases are low now, they have been busy with other health programmes. It is critical to keep up their morale and to ensure they are not exhausted,” he says.

BBMP Commissioner N. Manjunath Prasad had recently said that Bengaluru would get an additional 1,322 ASHA workers, more than doubling their numbers in the city. Meanwhile, Dr Sachidananda from RGUHS (Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences) said between the first and possible second wave, around 2,500 medical students had joined the final year of MBBS or became Post Graduates or started medical residencies in government hospitals – all of whom would be available throughout the state and in Bengaluru, to handle Covid-19 emergencies.

The assurance, however, has done little to lower the anxiety of ASHA workers. “So far, not one person has joined us in the hospital. Even if they come before a second wave, it would take time to train them and get them used to the area. It was because we had been working in the area for years that it became possible to respond quickly to calls of COVID positive cases,” says an ASHA worker who has been working in the city for six years.

That elusive incentive

The general chatter among health workers is about how their battle against the pandemic has left them exhausted. During the first wave, many found strength in the belief that the pandemic would not last long and life for them would return to normal, soon.

“To think of a second wave is demoralising when nothing has changed for us. There is no incentive nor is any safety equipment distributed. We’d have to put our lives on the line again,” says D. Nagalakshmi, State secretary of the Karnataka Rajya Samyuktha Asha Karyakarteyara Sangha.

Another ASHA worker who requests anonymity, summed up their predicament. “I took pride in my work, but soon started to ask myself if it is worth endangering myself and my family. Even my family kept asking me to quit. But, there are no other job opportunities for us now. What spurs us to continue now is that we will get vaccinated soon and this pandemic will end,” she says.

Also read: