Bengaluru has attracted people from all walks of life. In addition to long term inhabitants, it is a city for students, factory workers, small vendors, and sees a lot of migrant population. The Bangalore Urban district mostly comprises the Bangalore metropolitan area. In 2011, this district was 90% urban, and it may be assumed to be almost entirely urban in nature.

Understanding the healthcare needs of migrant workers

Migration is a complex process with far reaching effects on individuals, societies, and health systems. The urban migrant population often experiences significant barriers to accessing health services, including limited availability of services, financial constraints, language barriers, and discrimination.

Despite this, there is limited understanding of the health and healthcare needs and experiences of urban migrants, and how health systems can be reoriented to address these needs. Health research initiatives at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS) aim to address this critical gap by investigating ways to create pathways to integrate migrants into healthcare systems in Bengaluru.

Existing literature suggests that in many parts of the world, migrants face health inequities due to discrimination, social exclusion, legal status, gender inequalities, poor living and working conditions, language barriers, lack of information and absence of healthcare financing. Furthermore, concerns of accessibility, affordability, equity and entitlement reduce migrants’ ability to seek healthcare. Given this, researchers have acknowledged the need to examine migration as a social determinant of health.

Migrant health has been the subject of various international agreements in recent years. In parallel, there has been a growth in academic research in this area. However, this increase in focus at an international level has not necessarily strengthened the capacity to drive evidence-informed national policy and action in many low and middle-income countries.

The 2011 population of the Bangalore Urban district was 9.62 million, out of which 5.14 million were migrants, who arrived at different points in time. As Census 2021 has been delayed, the current population of the district is available only from estimates. The 2020 population estimate from WorldPop (1) is 10.9 million and the 2023 estimate by ESRI (2) is 12 million. If we assume that the migrant population fractions in the population stayed constant over the past decade, in 2023, there are an estimated 6.41 million migrants in the district as of 2023. 4.82 million would be the estimated number of migrants between the ages 15 and 59 in 2023.

(With inputs from Sooraj M Raveendran, IIHS- Urban Informatics Lab)

Tuberculosis as a reference point

Tuberculosis (TB) is an interesting disease to understand the functioning of health systems, especially public health systems, which essentially should have prevention at the core.

TB is caused by a bacterial infection and transmitted by airborne droplets. In layman language, in a country or a location with higher prevalence of TB, anyone breathing air will have the TB bacteria (Mycobacterium Tuberculosis) in their lungs. That is the reason, no one from India will test negative for Mantoux test (screening test of TB bacteria). Traces of TB bacteria in our systems does not necessarily mean we all are infected with TB. It simply means the air we breathe contains TB droplets released by active TB cases.

Of course, the concentration of these droplets will vary depending on the number of active pulmonary TB cases, congestion of the spaces we are in, whether the TB cases are on treatment or not; use of masks or not. That is the reason TB is an interesting disease to study, because just merely ingesting TB droplets will not cause disease, but our body will recognise the entry of new bacilli and set off an immune reaction (this is called primary infection). And most of the time, our body is equipped to nullify this infection with one’s innate immunity (in built immunity).

The problem starts when our innate immunity is faulty, and the primary infection progresses to become a full-fledged infection to become full blown TB disease. In this case, the host (the individual) has failed to protect his/her system from the infection and the infection has now spread to other organs or multiplied in one organ. This individual is also now capable of spreading the bacilli (TB droplets) afflicted with pulmonary TB (open case – cough or sneeze could release droplets).

This means, no one gets TB disease just like that. But it is a slow process and there are many steps where one can intervene, or health systems could intervene to prevent it from becoming a disease. Here is an explanation of how:

(a) Faulty immunity: The first hurdle is when the bacilli jumps over our first layer of defence – our immunity; post pandemic, we all know this term, and we also know what affects immunity. Lack of proper nutrition, long standing malnourishment, not well-adjusted work-life balance, lack of screening of underlying health conditions and rectifying them, underlying auto-immune disorders and comorbidities.

(b) Progression to TB disease: This process is slow, there are symptoms like low grade fever, weight loss, lack of appetite over a long period. These symptoms are often neglected for cold/ or minor malaise. For a well-functioning public health system, this must send a trigger to screen and follow up to avert a bigger health burden for the system as well as the individual/communities.

So, if we see a large number of TB cases or multi drug resistant TB cases, TB drop outs – we must know we have a faulty system – health systems, social equity, overall the interconnected system one lives in.

TB control initiatives in Bengaluru

TB is a major public health problem in India and Bengaluru is no exception to this. However, the public health services in the city are working towards providing efficient TB control services. Compared to other cities in India, the TB control initiatives in Bengaluru have been quite successful.

The Revised National TB Control Program (RNTCP) is the government program responsible for TB control in India. In Bengaluru, the program is implemented through the Bangalore TB Control Unit (BTCU), which operates under the auspices of the Karnataka State TB Control Society.

The national TB control programme is designed to cater to TB cases who have a valid proof for residence. This was designed for the health systems to follow up with the patients on treatment to check adherence to mitigate drug resistance and to maintain the cure rate for the patients on treatment. But, looking at the present time, this design backfired as most migrant residents in the city might not have a valid address proof of their current residence.

Namma Clinics are part of the TB control programme in Bengaluru. These primary healthcare centres provide diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up care for TB patients. They are expected to refer complicated TB cases to higher-level facilities as required.

The TB control programme in Bengaluru also has other components, such as private sector engagement, community involvement, and use of technology. Private sector providers are encouraged to notify cases to the BTCU (Bangalore TB control Unit) and follow the RNTCP (revised national TB control program) guidelines for treatment. Community members are sensitised about the disease and encouraged to seek care from government facilities. Technology is used for case detection, diagnosis, adherence monitoring, and drug-resistance testing.

TB estimates in Karnataka and Bengaluru

‘Yes! We Can End TB’ is the World TB Day’s theme for 2023. Looking at the post pandemic TB scenario in the country, and especially in Karnataka, it is quite concerning that while combatting COVID-19, all the other diseases were neglected. A disease like TB, which is slow and has a long infective phase and requires a long treatment period, any delay in screening (at the onset of the infection) and break in treatment is initiating a fission reaction. If the individual on treatment stops taking medicines, they might develop drug resistance and even death. The individual with symptoms who got delayed for screening, and hence diagnosis, would become an active source for transmission in the household/community.

In Karnataka, 184 persons per 100,000 are estimated to have medically treated tuberculosis, based on reports from household respondents. The prevalence of medically treated tuberculosis is lower among men (159) than among women (209) and is higher in rural areas (193) than in urban areas (171)- this is as per NFHS-5, 2019-21.

As per estimates, Karnataka’s TB cases have increased and are comparable to pre-COVID numbers. This is not an absolute number as almost 50% of the population seek healthcare in the private sector and data from the public and private sector is not merged. Of this, 17% of the notified cases in Karnataka are from Bengaluru. This is of concern, given urban health infrastructure is scattered and often excludes populations, who are newly integrated into the city (migrants, informal workers, temporary residents without ID proofs linked with the location of residence, informal settlements).

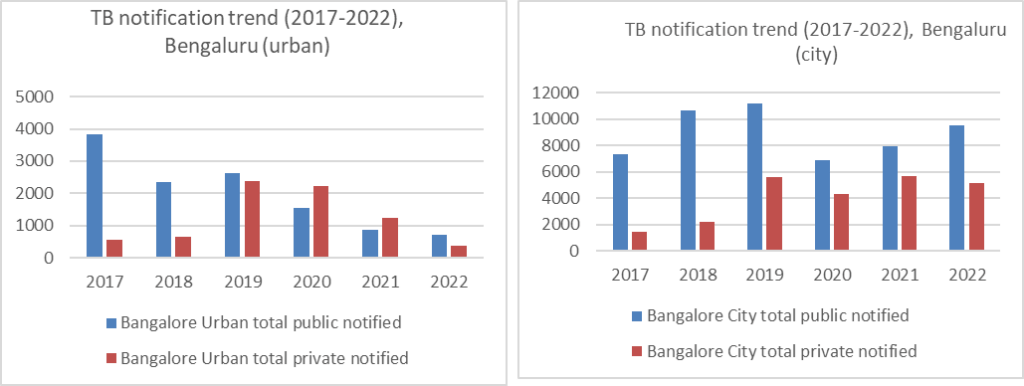

RNTCP database is updated up to 2018-19. In the absence of public databases on TB prevalence at district level, the author compiled notification data based on the Nikshay database. The number of cases as reported by the providers at public and private facilities through 2017-2022 shows:

Role of Namma Clinics

From the health systems part, primary healthcare systems in the urban areas are patchy, as Urban Health Centers (on the lines of Primary Health Centers [PHC] in the rural areas) do not have the entire urban population covered. RNTCP – the national TB control Programme runs under state run institutions with specific DOTS centres as the first point of contact for screening and diagnosing symptomatic cases for TB.

Read more: Govt took some action during COVID, but failed to address larger structural issues in healthcare

The newly launched 108 Namma Clinics to create first point of contact for primary healthcare in the city, is a good step but creates confusion for the community/individual seeking health care as this is not integrated with disease control programmes. Also, as a new referral system it will not be robust. As for the patients, we are adding more steps to cover before they finally could get diagnosed and start on medication (an important step to cut the transmission).

It is important to create a concerted effort for Bengaluru, to begin with, to integrate the care seeking pathways for TB. Only then could we think of ‘ending’ TB in the near future, if at all by 2030.

Healthcare schemes for migrants

Under the Ayushman Bharat scheme, migrants from different states can access healthcare services in the public domain when located in another state. The scheme is portable, which means that beneficiaries can access healthcare services in any empaneled hospital across the country. This makes it easy for migrants, who move from one state to another for work, to access healthcare services without any hindrance.

In addition to Ayushman Bharat, several state governments have also launched similar health insurance schemes, which are applicable to migrant workers. These schemes also provide coverage for hospitalisation expenses and can be availed by migrants when they move to different states.

However, it is important to note that migrant workers may face certain challenges when accessing healthcare services, particularly when language barriers or other cultural issues arise. The government and healthcare providers need to take necessary steps to ensure that migrant workers are not discriminated against and can access healthcare services as and when required.

Challenges of migrants in accessing healthcare

Migrants and informal workers in big cities face several challenges and barriers when accessing primary healthcare services in the public domain. Here are some of the most significant challenges:

1. Lack of documentation: Migrant workers and informal workers often do not have the required documentation to access healthcare services. This can be due to a lack of awareness or due to their temporary nature of work.

2. Language barriers: Migrants, who move from one state to another, may not be fluent in the local language, making it difficult for them to communicate their health problems in local health centres.

3. Lack of awareness: Migrants, particularly those who come from rural areas, may not be aware of the healthcare services available in the city. This makes it difficult for them to know where to go for treatment.

4. Discrimination: Migrants may face discrimination based on their ethnicity or language, making it difficult for them to access quality healthcare services.

5. High cost: The cost of healthcare services in private hospitals can be prohibitively high for migrants and informal workers. This forces them to rely on public healthcare services, which are often overburdened.

6. Accessibility: Many health centres in the public domain are located in urban areas, making it difficult for migrants and informal workers, who work in remote areas, to access healthcare services.

7. Inadequate infrastructure and facilities: Many primary healthcare facilities in the public domain lack adequate infrastructure and facilities, resulting in poor quality of care.

To address these challenges and barriers, it is important for the government and healthcare providers to take steps to improve access to primary healthcare services for migrants. This can be done by increasing awareness, providing language support, reducing the cost of healthcare services, improving infrastructure and facilities, and ensuring that healthcare services are not discriminatory.

However, in recent years, the government of Karnataka, has taken several measures to address public health issues in the urban areas of the city. These measures include building new primary health centres, implementing telemedicine programs, and increasing the number of hospital beds.

Although these measures have improved public health services in Bengaluru, there are still challenges that need to be addressed, such as shortage of doctors, the high cost of healthcare, and inadequate health infrastructure in some parts of the city. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for building robust public healthcare systems that are accessible to everyone.

Solutions to integrating migrants into healthcare systems

Overall, there is much room for progress, and it is important to continue investing in public health services in Bengaluru, and across India, to ensure that all citizens have access to basic healthcare services.

One of the primary objectives of Namma Clinics is to provide integrated primary healthcare services to all citizens, including migrants. However, there are several challenges that migrants face in accessing these services.

Firstly, language barriers can make it difficult for migrants, who do not speak the local language, to communicate their health concerns or understand medical instructions. Many clinicians in Namma Clinics are trained to provide services in multiple languages, but this service may not always be available.

Secondly, migrants may face difficulties in registering for services if they do not have the required documentation, such as proof of residence or identification documents. This can be particularly challenging for migrants, who are living in informal settlements or do not have a fixed address.

Finally, Namma Clinics may not always be accessible for migrants due to issues such as distance or lack of transportation. To address these challenges, there have been initiatives to provide language translation services in Namma Clinics and simplify registration procedures for migrants. However, more needs to be done to improve access to primary healthcare services for migrants in Bengaluru, especially those living in vulnerable conditions.

There is a need to establish a platform, which will include stakeholders from migrant communities, health systems, policy makers, and civil society organisations, for ongoing dialogue and advocacy for migrant health and healthcare needs. This platform can also be used to disseminate research findings and to identify and address barriers to healthcare access for migrants.

Active engagement from different stakeholders is required to make a significant contribution to existing knowledge on migrant health and healthcare in urban areas. By identifying the health needs and healthcare experiences of migrants, developing and testing strategies for integrating migrants into healthcare systems, and establishing a platform for ongoing dialogue and advocacy, healthcare access and outcomes for a highly vulnerable population can be improved.