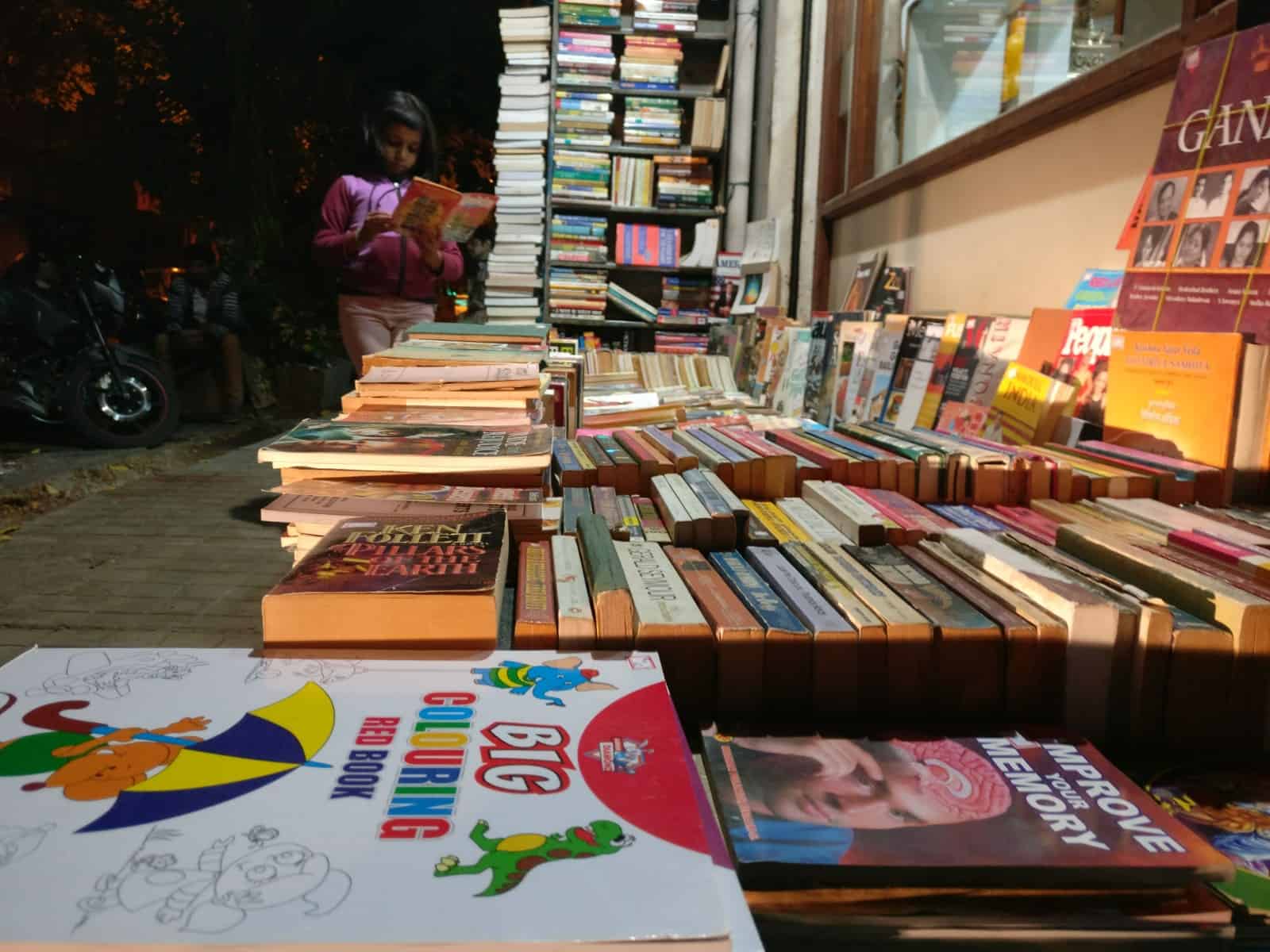

Roadside book vendors don’t stock Kannada books. Pic: Shree D N

Sampige Road, the road that leads to Malleshwaram, has something to offer to everyone. Nestled close to the famous Holige Mane and Bhagyalakshmi Gulkhan shop is an informal bookshop, next to the pavement. A quick look at the book collection on the Rajyothsava day reveals many English pulp fiction — but no Kannada books.

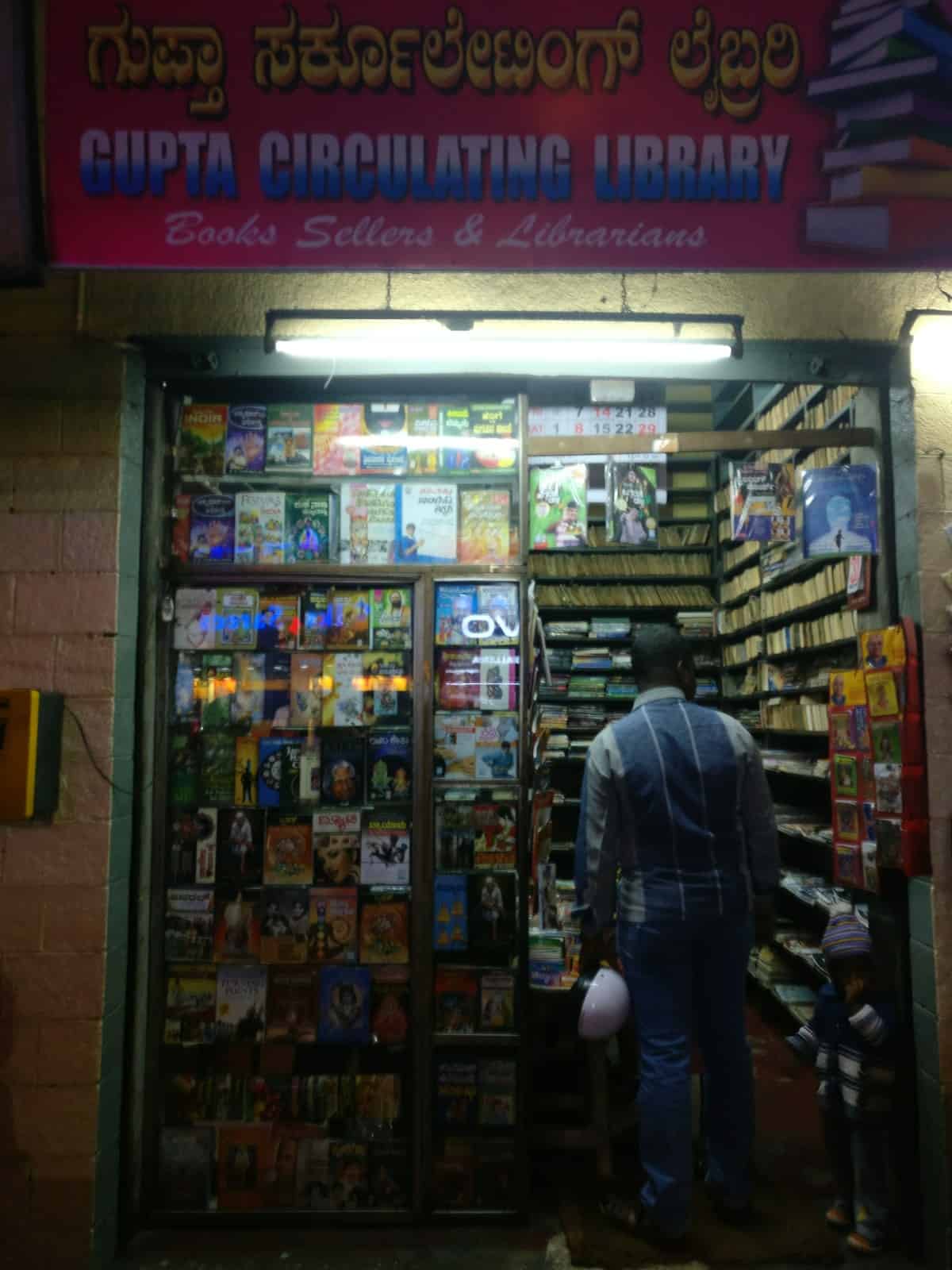

A few shops ahead, there is a board: ‘Gupta Circulating Library.’ The shop houses many old books — bound, numbered and neatly stacked, presumably constituting the library part of it. Many contemporary Kannada magazines, shloka and devotional literature occupy the front, visible part of the small shop.

Gupta, the proprietor, a man in his 60s seems uncomfortable talking about his sales and membership. He just says Kannada book buyers are becoming a minority with the passage of time. Library usage is not encouraging either. He handles a courier collection franchise, to help himself break even in the business.

What sells the most?

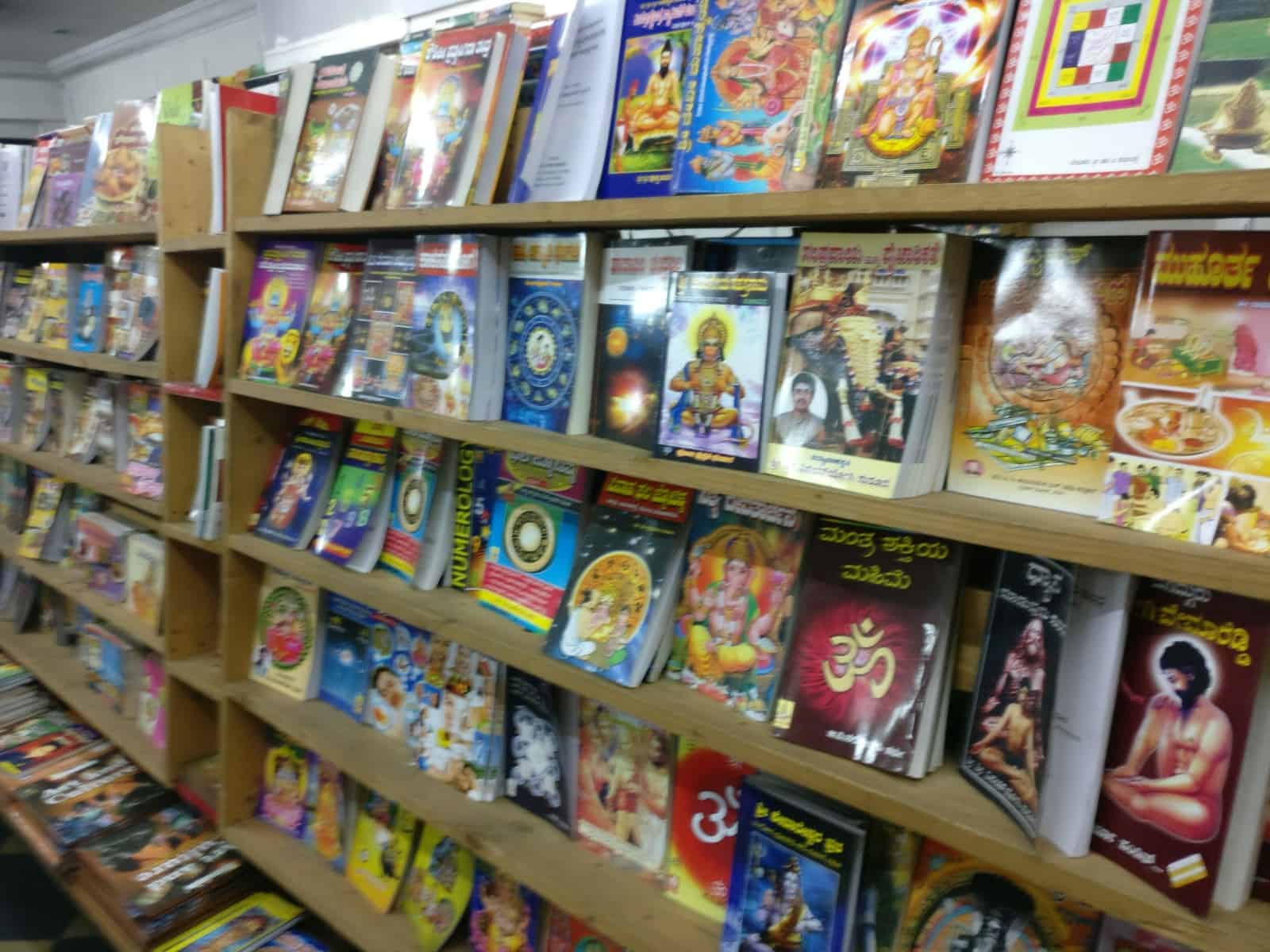

A few metres ahead, there is another formal bookshop: the Rainbow Book Exhibition. Though not comparable to big bookshops in the city, this shop stocks only what sells. A peek into the bookshop gives an idea about what sells in Kannada: shlokas, prayers, jokes, cooking, personality development, short stories of personalities and a few children’s collections are on the ‘hot’ category.

Some of the bestsellers among Kannada books. Pic: Shree D N

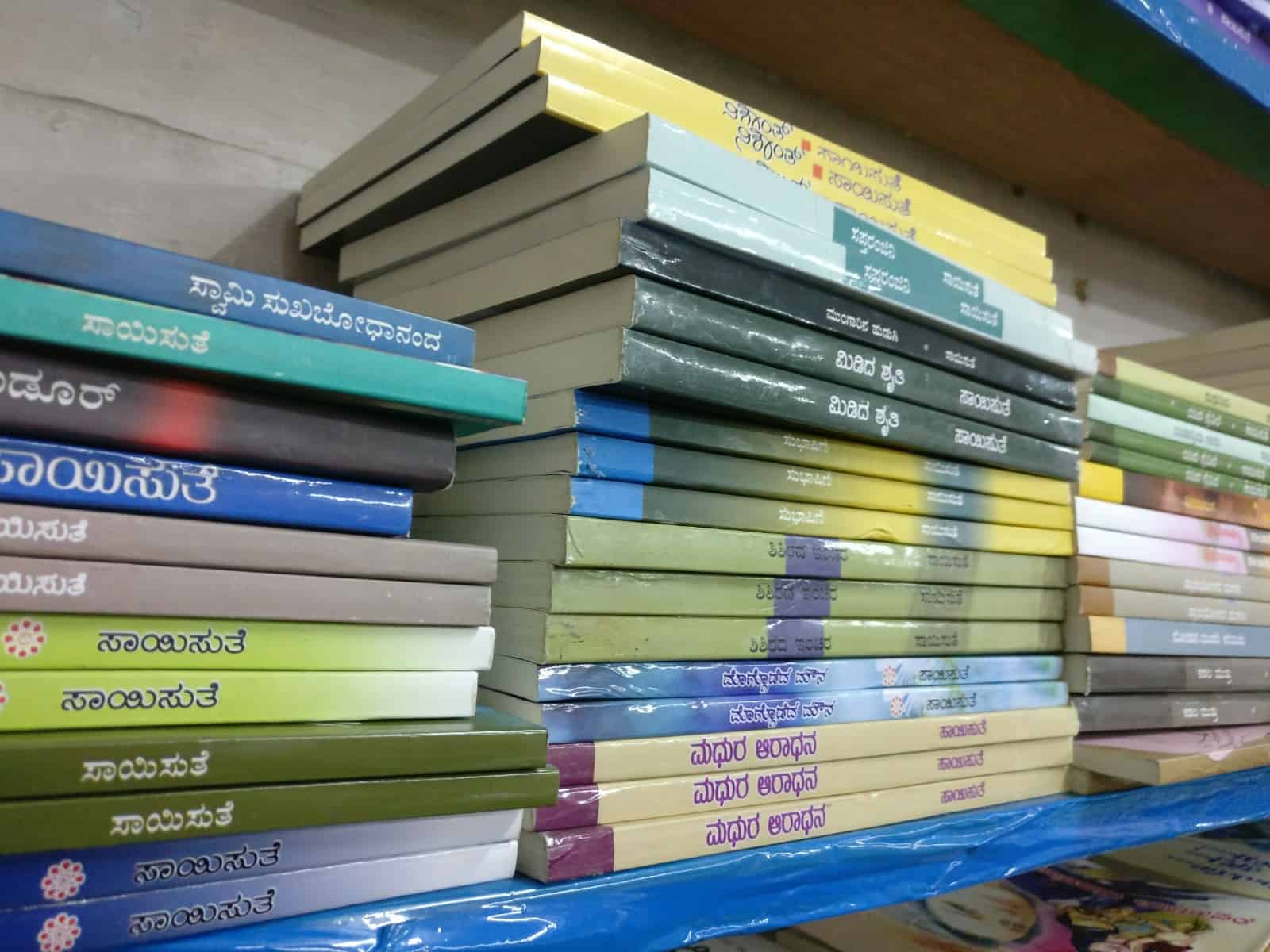

The neatly stacked Kannada novels written by Saisuthe and H G Radhadevi in a corner of the Rainbow bookshop give another insight into what sells: popular women-centric fiction is still a hit.

These are the books written by women and appeal to women. Many of them were written long ago, but are still in demand. Saisuthe, H G Radhadevi, Usha Navarathna Rram and Anupama Niranjana, whose stories revolve around a Bengaluru-centric lower and upper middle class culture and social situations, had a huge following of women as readers. Bookshops continue to sell many copies of these books.

However, the volume of sales of this category has also reduced with time, observes Bengaluru-based ex-techie-turned-author and publisher Vasudhendra Chandra. He says most women readers have shifted allegiance to television soaps, that portray a similar Bengaluru-centric upper middle class culture and language.

New writers don’t get enough exposure

Guruprasad D Narayana runs a bookshop, Akruthi Book House, that offers the visitors a curated collection of books. Along with women’s literature, he says the books written by Shivarama Karanth, Poornachandra Tejaswi and Lankesh are in the best seller category. There is no tradition of people asking for the books of new Kannada writers, he says.

Kuntady Nithesh, co-founder of the website Ruthumana, agrees with this. Along with publishing content on current topics, he has been working on introducing many new authors, through the website, by writing about them and giving space for their work. But this doesn’t reach expected readership levels. “What is already well-known gets read more and more,” he says.

Neatly stacked up bestseller books. Pic: Shree D N

How are new authors introduced to readers? Book reviews are great tools to achieve this. But, literary criticism is a dead space in Kannada, with literary magazines dying a quick death, and mainstream newspapers not doing enough to publicise new books, says Guruprasad.

Smaller bookshops are becoming a rarity these days, in most parts of Bengaluru. Book exhibitions do not take place at the desired scale. Even the Bengaluru Book Exhibition has stopped these days, so the space for publicising books has decreased, rues Guruprasad.

What are youngsters reading?

Vasudhendra says the quality of the books has been improving — be it the production, cover page design, layouts or writing. Sale of Kannada books has been increasing over the years. But the reason, Vasudhendra says, is the economy. The Kannada books buyers these days are generally employed and well-settled, and aged above 35 years. “It is the buying power they have due to employment and financial status, that’s at play here,” he says.

He says 80% of the Kannada book sales happens in Bengaluru. But, buyers below 25 years are rare. What are they reading? Are they not reading at all? Or does their interest lie elsewhere?

Sushrutha Dodderi is a Kannada writer, poet and blogger. He signed up with Dailyhunt, a Bengaluru-based app for news and information in English and other regional languages, to provide content on their platform. He says the readership is high for personality development articles, and light-reading topics like love, marriage and others.

Dailyhunt, in an email to this reporter, says 70% of its users are aged below 35. About 5 to 7% of the Kannada users are from outside India, and about 15% are from Indian states other than Karnataka. Out of the rest 75-80%, a sizeable chunk is from Bengaluru. The email attributed this data to Virendra Gupta, Founder and CEO, Dailyhunt.

This audience typically loves reading short Kannada articles on movies, celebrities, TV shows like Big Boss and cricket. Some regularly check their astrological predictions. However, the readership is not limited to entertainment and recreation. People also read about gold and fuel price fluctuation, current affairs like the Gauri Lankesh issue, Indo-China conflict and major stories about Modi.

Insufficient content, no cultural spaces to create interest

Guruprasad says the teens and youth visiting his shop buy books like Parisarada KathegaLu, or those in the thriller genre. If such books are written and publicised enough, they can hold the interest of the youth, he adds.

Sindhu Rao is a knowledge management professional living in Bengaluru. She thinks there is no atmosphere for children to read and write Kannada. It takes a lot of effort from parents to make children read Kannada, as the language is not taught in schools.

Libraries have lost sheen. Pic: Shree D N

Vasudhendra explains this further. The education system needs introduction of Kannada as a language in school, without which Kannada will die. If children are not initiated into Kannada in school, they will not be introduced to reading it. Vasudhendra foresees this affecting the language adversely.

He says this is the scenario across the nation. Everywhere, even in Hindi belts, Indian languages are not reaching new readers, in an atmosphere where new English novels sell like hot cake, irrespective of the quality of literature. The problem lies in the social and educational system that prioritises English, and the government that doesn’t push vernacular languages at school levels.

Migrants are not a threat to Kannada

A language cannot be forced on anyone, especially on those who have migrated to the city. Migrants are not a threat to Kannada. Learning the language should be voluntary, says Vasudhendra.

Sindhu says the problem is the education system in Karnataka itself. “Learning a language is not at all difficult for kids. It is okay even if the teacher teaches badly but they should learn the basics of the language in school itself, compulsorily. Else there is no future for the language,” she adds. She feels Kannada should be made compulsory as a language in the schools.

Radhika Ganganna, a techie from Basaveshwaranagar, agrees. “Look at the NRI Kannadigas. They have the need to learn and protect the language, so they learn Kannada by conducting various activities,” she points out. Language is a part of one’s identity, without which there will be a deep crisis, she fears.

Vasudhendra thinks a language protects the health of a society and holds it together. There will be a deep problem when this fabric is torn off, he adds. The NRI children visiting India carry huge English literature books as their schools have mandated reading novels. Language is so important in all cultures across the globe.

But, “we are losing the language,” he says. The reason, he says, is us. “It’s our own blind mistakes that are leading to this situation,” says Vasudhendra, pointing at how fanatic chasing of English and foreign languages is killing local languages, not just in Bengaluru but across India. Government schools are breaking down. Nobody cares for Kannada in private schools.

There are not enough cultural spaces in Bengaluru that create interest among new readers or new learners to read Kannada and to inculcate love for the language. As a result, the new crowd in their twenties is not reading serious Kannada literature. Initiatives like VividLipi and Ruthumana have been trying to help with more audio-visual content, and more such efforts are required, says Sindhu.

Literature beyond language barriers

“Kannada stories have seen the trend shift from rural-based tales to more urban settings. Clearly, we have readership here [in city], like every other language. And these stories are being added to our anthology and heritage of 2,000 years and more,” says Vikram Hathwar, a Kannada techie-cum-writer.

Vikram Hathwar was one of the chosen panellists for the recently concluded Bengaluru Literature Festival (BLF). “We had three sessions in Kannada. I saw about hundred people in each of them. That’s a good number. I was surprised because I had expected fewer people,” he says.

Yet, “the prism of numbers to measure popularity, though right to a certain extent, offers a narrow narrative. U R Ananthamurthy often said he wrote for two people who knew him. To my mind, any literature is popular even if it has just five loyal readers,” says Hathwar.

Meanwhile, there is a positive trend not so observed or celebrated: some part of Kannada literature is reaching a wider audience. English versions of Ghachar Kochar by Vivek Shanubhag, or Mohanaswamy by Vasudhendra have been popular at a different level. “The increasing popularity of translated works means we have also had readership for our stories among the readers not familiar with the language,” Vikram adds.

What’s needed to take Kannada to a popular level?

There are better ways to propagate a language than coercion. “Even Tamilians had kept the song ‘Anisuthide Yako Indu’ as their caller tune, when Mungaru Male movie was released,” Vasudhendra adds, stressing on what a good movie can do to propagate the language.

The government is not doing enough to protect the language, and to popularise it, without coercive methods. “We have Kannada Pradhikara and all other institutions, but I could find no one to even teach Kannada at my apartment level,” he says.

Radhika Ganganna is a techie from Basaveshwaranagar. Abhyaasa is a Kannada literature enthusiasts’ club she is involved in. Monthly book reading sessions and discussions are a part of Abhyasa activities. “There are members who started reading serious literature just because of Abhyaasa,” she says. They became influenced by the nuanced and serious discussions taking place in the sessions and got attracted towards litterateurs like Shivaram Karantha and K V Puttappa, she explains.

Such individual and community efforts are a silver lining in the scene. However, clearly, there is a lot that can be done by the government to help Kannada flourish. With the government reiterating its intent to make Kannada a compulsory language in schools, will Kannada find a way to thrive among young generation? Time alone will tell.

Note: Manasi Paresh Kumar contributed to this article.

A language exists so that people can use it. People don’t exist so that a language can survive. If people find a language useful, it will survive. Else, it will die. Simple as that.

Good article. Made me recall our formative years, nearly 30-35 years back in a rural Malnad area where we used to read kannada books for the love of reading and nothing else. We had outgrown Saisuthe, HG Radhadevi, S. Mangala Satyan kind of stuff early enough and fell irrecoverably into the magic literature of Yashwant Chittal, Shanthinath Desai, U.R Ananthamurthy and the like. The books we loved then are still with us, both in the shelf and in the mind. Reading this article I felt where are our present youngsters leading to? I feel they miss a lot. Dont know whether I am right or wrong. But serious reading of good books, kannada or English definitely changes a person, for the better, I feel. Thanks for the article narrating the state of affairs in reading habits of present generation…