Pattandur Agrahara, a huge lake off ECC Road in Whitefield, is in danger of getting swallowed by land sharks. The lake is encroached by vested interests, and is also being dug up by the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike to build an 80-feet Road. Citizens have been protesting and taken the matter to court to save the lake.

The history of Pattandur Agrahara Kere

An almost 1000-year-old inscription stone dating back to 11th century was found in Pattandur Village recently. It threw an important insight into a dispute which is in court right now. Udaya Kumar PL, a Bengalurean who has been documenting the inscriptions in Bengaluru city, has crosschecked the inscription with Epigraphia Carnatica, to get more insights.

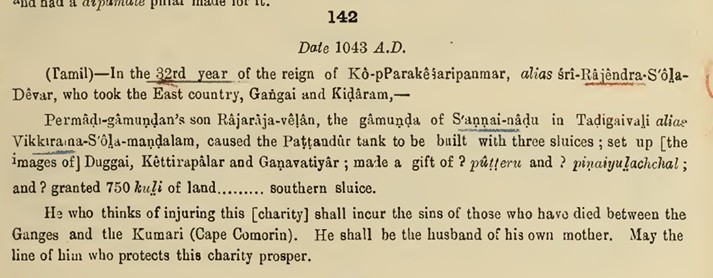

Epigraphia Carnatica is a set of books on epigraphy of the Old Mysore region of India, compiled by Benjamin Lewis Rice. According to this, the engraving says this:

Source: Epigraphia Carnatica

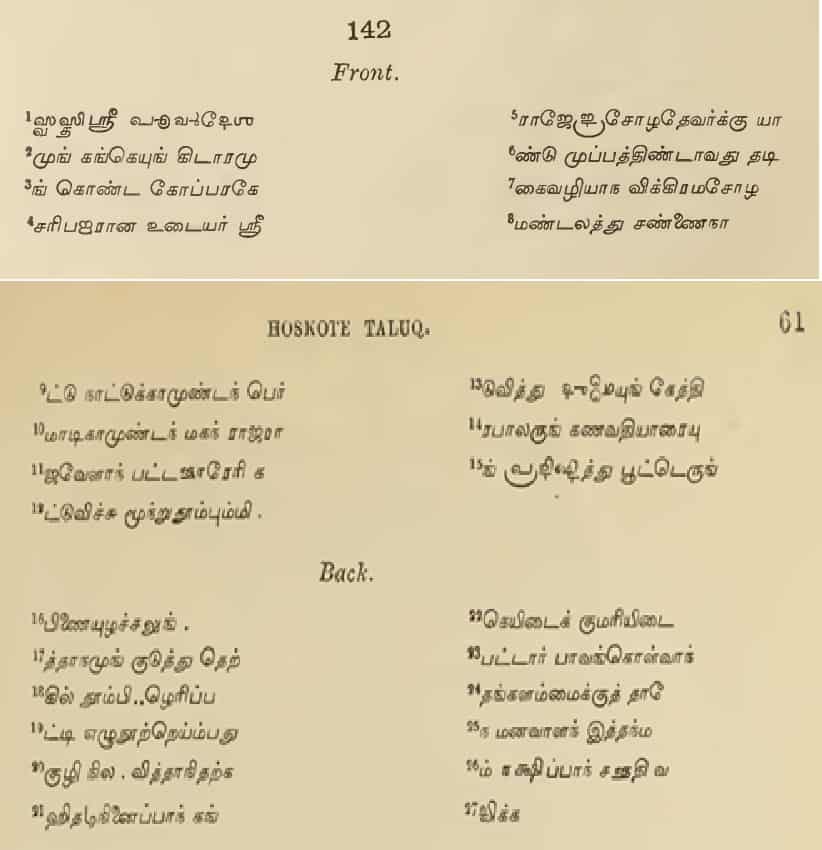

Tamil write up on the inscription. Source: Epigraphia Carnatica

The stone inscription mentions the name of the king Rajendra Chola – I, who, in his 32nd year of ruling, gifted land for the construction of the Pattandur Agrahara lake. He ordered the installation of idols of three deities, including goddess Durga, Kshetrapala and Ganapathi, around the tank in Pattandur, that had three sluices. It also warns that those who try to damage the ‘charity’ (tank) shall inherit the sins of those who have died between the Ganges and Cape Comorin (present Kanyakumari). “He (one who damages the ‘charity’) shall be the husband of his own mother. May the line of him who protects this charity prosper,” says the inscription.

This was in 1043 AD. After 975 years, the government of the day has been struggling to take the ownership of the tank constructed by erstwhile rulers, which is technically a government property.

Source: Save Pattandur Lake FB group

What do experts say?

A British-era map from 1865, recovered from a landowner in the area clearly outlines the lake area and also the rajakaluves (storm-water drains) connecting to it.

V Balasubramanian, Chairman of Karnataka’s Task Force for Recovery and Protection of Public Lands says that records clearly state that the land being encroached is lake bed. “There are many orders of the Courts that tank bed lands cannot be used for any other purpose. It is quite tragic that valuable tank bed lands are being stolen by greedy persons and the Government is allowing it without taking the matter to the Supreme Court,” he said.

“Revenue records as available at the office of the Tahsildar, clearly indicate that Pattandur Agrahara, Survey No 54, has been classified as a lake way back in the 1950s,” says CEO of Namma Bengaluru Foundation, an organisation that aims “to make Bengaluru Better.”

The legal history of land dispute

The new survey number 54 is how the Pattandur Agrahara lake has been identified in government records during recent times. Its existence has been further validated by an 1865 British Survey map that clearly marks the lake bed besides the A T Ramaswamy report. Yet there have been legal claimants to lake who say they had cultivated it for agriculture.

Documents furnished by the group Save Pattandur Lake placed in the public domain mention a claim made by one Venkatappa claiming permanent tenancy which was thrown out by the Special Deputy Commissioner for Abolition of Inams.

The second claim came in 1962, when a lady Ramakka lay claim to twenty guntas of the lake bed. This too was rejected by Special Deputy Commissioner on the grounds that private ownership cannot be allowed of a lake bed.

In 1995, another claim was filed by a citizen Munivenkatappa claiming occupancy of 11 acres and 20 guntas. A civil court had delivered a verdict in his favour in a civil suit. Munivenkatappa had submitted sale deed copies to support his claim. He even produced a directive from the Land Tribunal from 1980, which stated that since the land had lost the characteristics of a tank bed about sixty years back, there was no impediment for the registration of occupancy.

This article on Bangalore Mirror explains the details of the land transactions. The Chief Secretary had mentioned in an affidavit that there was no such directive from the Land Tribunal, but this was hidden from the court by officials. In 2007, a judgment by Justice N Kumar questioned the existence of such an order. The citizen group that is fighting against the handing over the property to a private citizen argue that since the land has been identified as a lake bed multiple times, the gift deeds are not valid, as previous claims to the lake bed have been rejected on this very ground.

However, a division bench headed by BS Patil and Raghavendra S Chauhan, in a hearing held on May 30 2018, just a day before BS Patil retired, issued an order that said the Revenue Department must transfer the revenue records of this land to private parties who have laid claim to the lake. The decision of the HC appears to stem from an earlier decree made in 2016 that declared the lake to be private.

The next hearing held on June 5, 2018, however brought some respite. The new bench decided that the new judge who was put on the case needed more time to study the subject.

Source: Save Pattandur Lake FB group

A group of activists under the banner ‘Save Pattandur Agrahara Lake’ has been campaigning for the cause of the lake and sharing information and updates on hearings.

What’s in store?

The area has been identified as a lake in every document for the last 100 years, says Sandeep Aniruddhan of the Save Pattandur Agrahara Lake group. “If it wasn’t a lake, it shouldn’t have been identified as one, in the records for so long,” he adds.

All candidates contesting from Mahadevapura constituency including the MLA Aravind Limbavali, agreed that the lake was being encroached and needed to be cleared. Arvind Limbavali, in the beginning, promised to look into the matters of the lake.

However, the citizen activists claim that when they went to him to talk about the lake, he rallied for the road. He said that an 80 feet road was required to control traffic in the area, they said.

But at a recent protest, Arvind Limbavali promised that they would not allow anybody to encroach the area and will “fight until the land is given back to the lake.”

Local BBMP ward corporator Muniswamy S also participated in the protest and said that corruption is the prime reason for the destruction of the lakes. “How will our children live if we don’t conserve nature? Garden city has become garbage city,” he said.

This article was curated by Kathelene Antony and Manasi Paresh Kumar.